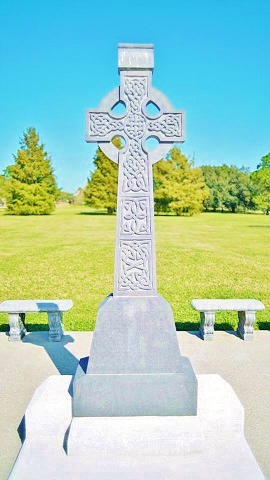

Twenty seven years ago, a Celtic Cross cut of marble from County Kilkenny, Ireland, was dedicated to the immigrant Irish workers who dug New Orleans’ New Basin Canal. The work was completed in 1838, after six years of labor. The canal connected Lake Pontchartrain with the interior of the city to promote commerce; today, the canal is filled. Commerce moves through the city still, though differently. In that former canal space, a beautiful monument stands in the neutral ground, on the grass between West End Boulevard going north and Pontchartrain Boulevard going south. This monument is an actual piece of the country of Ireland, shaped by Irish hands. From the powerful force required to break the block away to the heartbreaking care required for the intricate carvings, this stone monument mirrors the history of New Orleans, and on a larger scale, of America as well.

Thanks to the Irish Cultural Society of New Orleans who spent the time and effort to raise $20,000 to finance the cross. It is jarring to think that the cost of that canal is measured in lives as well as dollars and time. The cost in lives is significant; the exact number of men lost, primarily Irish, is unknown. Estimates vary from hundreds to tens of thousands. When mosquito-born diseases like cholera and yellow fever plagued the city, these men were hit hard, as they were working in swamp water up to their hip. They went to work sick to dig a channel that would innervate New Orleans. There is honor in that, and the sacrifices made to get to the city’s heart speak to an understanding of disaster shared by New Orleans and the country of Ireland.

Between economic and natural disasters, New Orleans and Ireland have experienced events that range from severe damage to utter catastrophe. The Great Famine, 1845-1851, caused an exodus from Ireland, with a horrific new reality for those leaving or staying. Hurricane Katrina had a similar effect on New Orleans in 2005, also growing the north shore along with the rebuilding process.

The Irish immigrants who died digging the New Basin Canal were men who left their native country in the days before the Great Hunger, as conditions became more desperate in Ireland – politically, economically, and in every aspect of the physical, mental and emotional health of the people. Tensions tend to build for long periods of time before devastation. The question “what caused it?” is different every time you ask; how far back to look?

I’m sure the men who died digging the canal thought of their family back in Ireland, even as they passed on and returned to the ground of their workplace. I’m sure there were good times, hope and an opportunity to balance the desperation of that work. A labor union grew, and the opportunity to be as big as you could dream was before them, as well as the risk. Tragedy permeated all levels of existence, deeply into art as an expression of emotion. The following song places the number of casualties at 10,000, which may not be an exact count–but the permeation into the psyche is strong and gives evidence to the level of grief. “Ten thousand Micks, they swung their picks/ to dig the New Canal/ but the cholera was stronger ‘n thay/ An’ twice killed them awl”.

It’s not an easy song to listen to. Many of the men who are the subject of this popular song were in the very beginning phase of changing nationality. That’s an enormous transition, likened to being on the neutral ground in between – probably thinking of their homeland constantly. As New Orleans shows a continuous affinity for saints, the immigrants revered Saints Patrick and Brigit. Maman Brigitte is the Haitian/New Orleans Voodoo spirit adopted directly from the ancient Irish Goddess Brigid. There is significant connection when theologies intermarry, one usually formed by a bond of labor and tragedy.

The Great Famine that changed Ireland changed America too, by extension. The men commemorated by the Celtic Cross here in Louisiana, Irish in origin but American at death, is but one example of how much the two countries share. The marble cross stands as memorial to the men who worked day after day to build a connection, carrying on their job while singing one hell of a work song. Perhaps November 4th will become an anniversary in both New Orleans and Ireland, one that commemorates the themes of sacrifice, suffering and respect of shared ancestors that builds a beautiful legacy. – By Lindsay Reed

Photos by Hunter Thomas