Covington History segment provided by local historical writer Ron Barthet.

View Ron’s blog Tammany Family here.

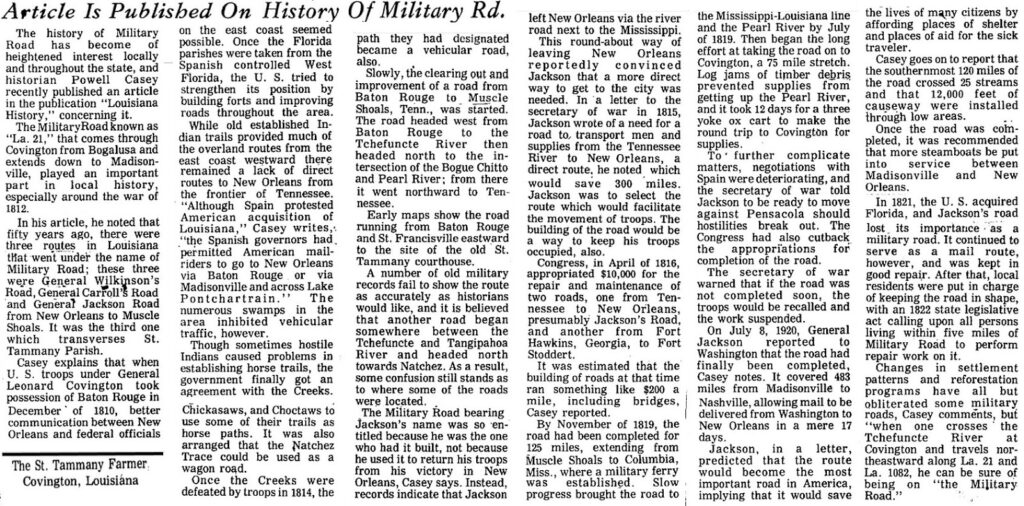

Historian Powell Casey extensively researched the history of Military Road (La. Hwy. 21) and once gave a presentation to the St. Tammany Historical Society detailing his findings. He later published a more extensive report in a statewide historical publication, and I wrote a newspaper article summarizing it. Click on the image of the article below to view a larger version of the article, which was published in 1974. A text version of this article is found below.

The history of Military Road has become of heightened interest locally and throughout the state, and historian Powell Casey recently published an article in the publication “Louisiana History,” concerning it.

The Military Road known as “La. 21,” that comes through Covington from Bogalusa and extends down to Madisonville, played an important part in local history, especially around the war of 1812.

In his article, he noted that fifty years ago, there were three routes in Louisiana that went under the name of Military Road; these three were General Wilkinson’s Road, General Carroll’s Road and General Jackson Road from New Orleans to Muscle Shoals. It was the third one which transverses St. Tammany Parish.

Casey explains that when U. S. troops under General Leonard Covington took possession of Baton Rouge in December of 1810, better communication between New Orleans and federal officials on the east coast seemed possible. Once the Florida parishes were taken from the Spanish controlled West Florida, the U. S. tried to strengthen its position by building forts and improving roads throughout the area.

While old established Indian trails provided much of the overland routes from the east coast westward there remained a lack of direct routes to New Orleans from the frontier of Tennessee. “Although Spain protested American acquisition of Louisiana,” Casey writes,-, “the Spanish governors had permitted American mail-riders to go to New Orleans via Baton Rouge or via Madisonville and across Lake Pontchartrain.” The numerous swamps in the area inhibited vehicular traffic, however.

Though sometimes hostile Indians caused problems in establishing horse trails, the government finally got an agreement with the Creeks. Chickasaws, and Choctaws to use some of their trails as horse paths. It was also arranged that the Natchez Trace could be used as a wagon road. Once the Creeks were defeated by troops in 1814, the path they had designated became a vehicular road, also.

Slowly, the clearing out and improvement of a road from Baton Rouge to Muscle Shoals, Tenn., was started. The road headed west from Baton Rouge to the Tchefuncte River then headed north to the intersection of the Bogue Chitto and Pearl River; from there it went northward to Tennessee. Early maps show the road running from Baton Rouge and St. Francisville eastward to the site of the old St. Tammany courthouse.

A number of old military records fail to show the route as accurately as historians would like, and it is believed that another road began somewhere between the Tchefuncte and Tangipahoa River and headed north towards Natchez. As a result, some confusion still stands as to where some of the roads were located.

The Military Road bearing Jackson’s name was so entitled because he was the one who had it built, not because he used it to return his troops from his victory in New-Orleans, Casey says. Instead, records indicate that Jackson left New Orleans via the river road next to the Mississippi.

This round-about way of leaving New Orleans reportedly convinced Jackson that a more direct way to get to the city was needed. In a letter to the secretary of war in 1815, Jackson wrote of a need for a road to, transport men and supplies from the Tennessee River to New Orleans, a direct route, he noted which would save 300 miles. Jackson was to select the route which would facilitate the movement of troops. The building of the road would be a way to keep his troops occupied, also.

Congress, in April of 1816, appropriated $10,000 for the repair and maintenance of two roads, one from Tennessee to New Orleans, presumably Jackson’s Road, and another from Fort Hawkins, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert. It was estimated that the building of roads at that time ran something like $200 a mile, including bridges, Casey reported.

By November of 1819, the road had been completed for 125 miles, extending from Muscle Shoals to Columbia, Miss., where a military ferry was established. Slow progress brought the road to the Mississippi-Louisiana line and the Pearl River by July of 1819. Then began the long effort at taking the road on to Covington, a 75 mile stretch. Log jams of timber debris prevented supplies from getting up the Pearl River, and it took 12 days for a three yoke ox cart to make the round trip to Covington for supplies.

To further complicate matters, negotiations with Spain were deteriorating, and the secretary of war told Jackson to be ready to move against Pensacola should hostilities break out. The Congress had also cutback the appropriations for completion of the road. The secretary of war warned that if the road was not completed soon, the troops would be recalled and the work suspended.

On July 8, 1820, General Jackson reported to Washington that the road had finally been completed, Casey notes. It covered 483 miles from Madisonville to Nashville, allowing mail to be delivered from Washington to New Orleans in a mere 17 days.

Jackson, in a letter, predicted that the route would become the most important road in America, implying that it would save the lives of many citizens by affording places of shelter and places of aid for the sick traveler.

Casey goes on to report that the southernmost 120 miles of the road crossed 25 streams and that 12,000 feet of causeway were installed through low areas. Once the road was completed, it was recommended that more steamboats be put into service between Madisonville and New Orleans.

In 1821, the U. S. acquired Florida, and Jackson’s road lost, its importance as a military road. It continued to serve as a mail route, however, and was kept in good repair. After that, local residents were put in charge of keeping the road in shape, with an 1822 state legislative act calling upon all persons living within five miles of Military Road to perform repair work on it.

Changes in settlement patterns and reforestation programs have all but obliterated some military roads, Casey comments, but “when one crosses the Tchefuncte River at Covington and travels northeastward along La. 21 and La. 1082, he can be sure of being on “the Military Road.”

Wikipedia also had an article on the Military Road, which goes like this:

Jackson’s Military Road was a 19th-century route connecting Nashville, Tennessee, with New Orleans, Louisiana. After the War of 1812, it was improved with federally-appropriated funds. The road was named for Andrew Jackson, hero of that war’s Battle of New Orleans.

Construction

The appropriation for Jackson’s Military Road was made on April 24, 1816:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That the sum of ten thousand dollars be and are hereby appropriated, and payable out of any moneys in the treasury not otherwise appropriated for the purpose of repairing and keeping in repair the road between Columbia, on Duck River in the state of Tennessee, and Madisonville, in the state of Louisiana, by the Choctaw Agency, and also the road between Fort Hawkins, in the state of Georgia, and Fort Stoddard, under the direction of the Secretary of War.

On September 24, 1816, William H. Crawford, Secretary of War, informed General Andrew Jackson, who was then commanding the Army district at Nashville, of the appropriation, and directing that $5,000 be spent on the road to Louisiana. He noted that “I have received no information of the length of this road, the nature of the country through which it passes, or its present state. If there are many bridges to be erected the appropriation will be inadequate to the object. In that event the employment of a part of the troops may become necessary.”

Jackson was officially in charge of the entire construction, including the First and Eighth Infantry and the artillery detachment who supplied the labor. However, much of the construction was supervised by his subordinates. Captain H. Young surveyed the route, completing this task by June 1817. Bridges were indeed needed, and an additional $5,000 was appropriated in March 1818. Major Perrin Willis took command of the construction gang, then numbering about fifty, in April 1819, when the road reached the Pearl River. The road was completed in May 1820, after 75,801 man-days of labor.

Description

The Tuscumbian of Tuscumbia, Alabama, printed a description of “General Jackson’s Military Road” on November 12, 1824. It states its length at 436 miles (Nashville to Madisonville) or 516 miles (Nashville to New Orleans), 200 miles (320 km) shorter than the historic Natchez Trace. The article describes the construction gang as averaging 300, “including sawyers, carpenters, blacksmiths, etc.” The road included 35 bridges and 20,000 feet (6,100 m) of causeway, particularly through the swamps of Noxubee County, Mississippi.

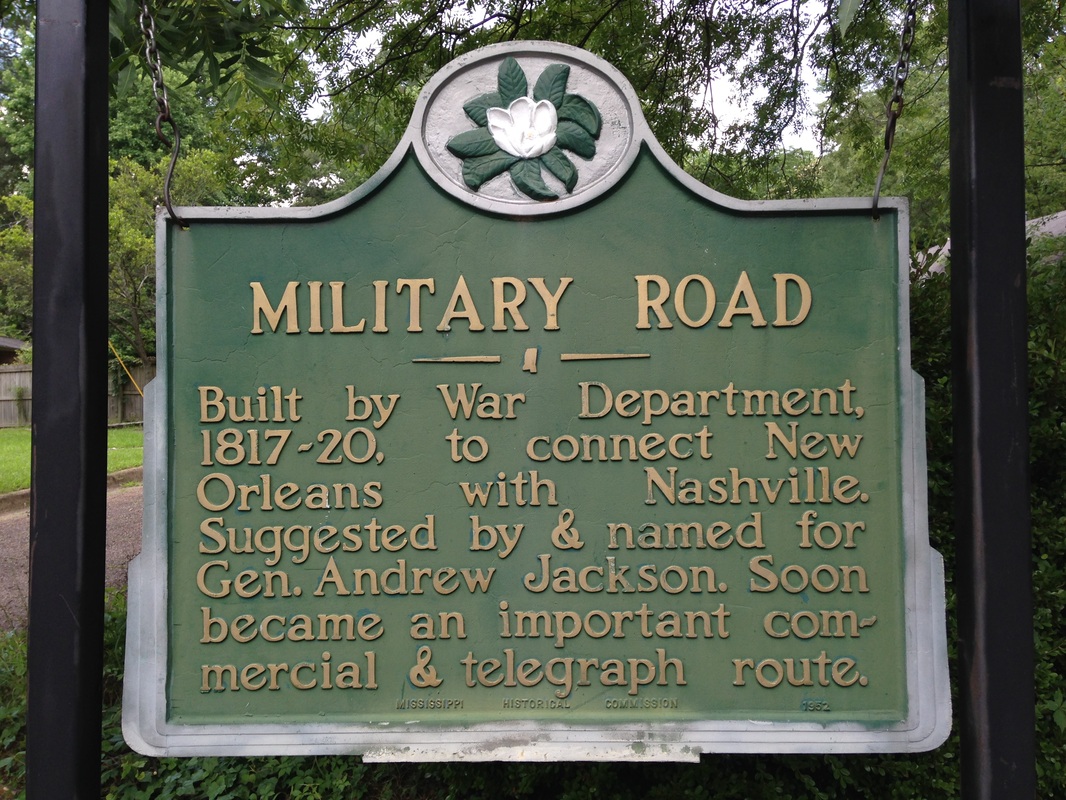

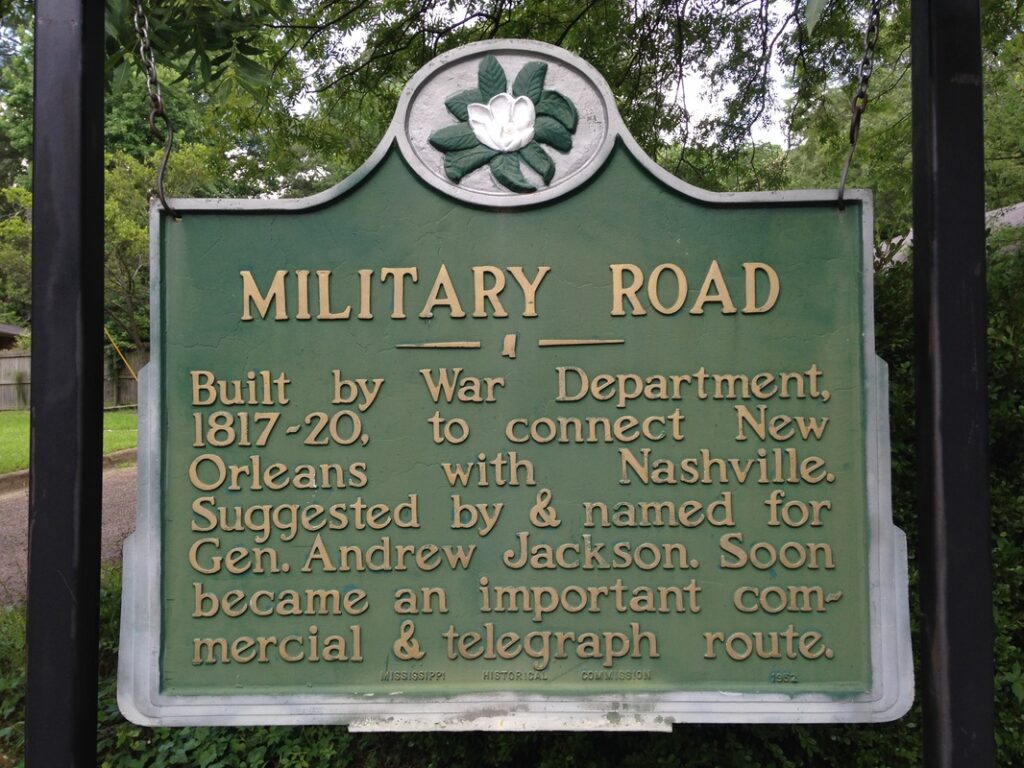

This historical marker is in Columbus, Mississippi. Jackson’s Military Road, surveyed by Captain Hugh Young, ran from Cotton Gin Port to Madisonville, LA. Photo Source: MississippiMarkers.com

From Columbia, Tennessee, the Military Road passed through Lawrenceburg and crossed the Tennessee River at Florence, Alabama. The road intersected the Gaines Trace at Russellville, Alabama (where it still exists as Jackson Avenue). It then cut cross-country through then-mostly-unoccupied lands of Alabama and Mississippi, including some still owned by the Choctaw Nation.

In Hamilton, Alabama, “Military Street” marks the route of the Military Road. The road crossed the Tombigbee River in Columbus, Mississippi; the route still exists in that town and still bears the name “Military Road” from the Alabama border to downtown. West of the Tombigbee, the road passed through lands later assigned to Lowndes, Noxubee, Kemper, Newton, Jasper, Jones, Marion, and Pearl River Counties, before crossing into Louisiana at the Pearl River twenty miles (32 km) west of today’s Poplarville, Mississippi. The road then passed directly from the future site of Bogalusa, Louisiana, to Madisonville, Louisiana, on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

Jackson’s Military Road declined in importance in the 1840s due to disrepair and the difficult route through the swamps of the Noxubee River, and it was largely replaced by the Robinson Road. (Available information about Robinson Road is scant, but it apparently linked Columbus, Mississippi, and Jackson, the city which became Mississippi’s capital in the early 1820s.)

The route later became part of the Jackson Highway.

Check out Ron Barthet’s blog Tammany Family for more great local history!